Typical Year Forecasting of Electricity Prices

Improve your energy project modelling with this simple & flexible forecasting technique.

Energy prices are volatile - the price of gas, oil and electricity can all change significantly year on year. Yet the energy industry ignores this year on year volatility when modelling investment decisions in energy projects.

This exposes projects to a significant source of hidden error in the form of variance in financial model results, leading to the wrong projects being built.

This post introduces a simple solution to this problem in the form of a typical year forecast.

You can find supporting materials for this work at adgefficiency/typical-year-forecasting-electricity-prices.

What is a Typical Year Forecast?

A typical year forecast uses historical data to create a single, synthetic year of data.

This single year forecast is suitable for use in business case modelling of energy projects - it’s not suitable for short term dispatch of energy assets.

A typical year forecast has the following advantages:

- simple to create - no machine learning, gradients or iterative calculations,

- interpretable - easy to understand why one sample is selected over others,

- realistic - the forecast is made from real historical data,

- domain flexible - can be used with any time series,

- statistically flexible - can use a range of statistics to define what typical means.

A typical year forecast has the following disadvantages:

- data quantity - requires at least 2 years of historical data,

- domain knowledge - requires selection & weighting of statistics.

An example of a typical year forecast is a typical metrological year (TMY) forecast, used to create a dataset of typical year of weather. TMY forecasts are commonly used in modelling solar generation or building energy use.

The idea & inspiration for this post came from using the TMY forecast produced by Solcast - thanks Solcast for the inspiration!

The Problem with the Standard Industry Approach

Estimating the economic performance (simple payback, IRR, NPV or rate of return on capital) of an investment in an energy project requires combining two models - a technical model and a financial model.

Commonly the technical model will model a single year in isolation, and is used as an input to the financial model.

The financial model will model multiple years over time (to model economic return over time), using the technical results as the basis for the first year with the financial inputs (such as prices) forecasted forward based on the single year technical results.

In the absence of forecasted energy prices across the future project lifetime, energy prices are often modelled in a similar way to the technical model - taking a single reference year of prices and forecasting them forward with assumptions of inflation.

A simple example of how a technical & financial model combine is given below:

- a technical model outputs annual savings of

150 MWhof electricity, - we assume electricity prices at

100 $/MWh - capital investment is estimated at

$ 25,000.

The technical inputs & price assumptions are then forecast forward (here without inflation) to calculate cumulative savings:

| year | capex | savings_mwh | price | savings_$ | cumulative_savings_$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 25000 | 150 | 100 | 15000 | -10000 |

| 1 | 0 | 150 | 100 | 15000 | 5000 |

| 2 | 0 | 150 | 100 | 15000 | 20000 |

| 3 | 0 | 150 | 100 | 15000 | 35000 |

It’s not common to see both the project capex and savings in the same year (usually you need to build something before it gives a saving) - for this simple example please forgive this!

Why Using The Most Recent Prices is Wrong

Choosing the reference year for prices is commonly done by:

- taking the most recent prices,

- taking the most recent full calendar year of prices,

- taking the prices that align with the technical model.

If we were setting up our model in November 2022 with a technical model based on 2019 data, the standard industry approach would likely be one of the following:

- the most recent prices - October 2021 to September 2022,

- the most recent calendar year - January 2021 to December 2021,

- prices that align with the technical data - January 2019 to December 2019.

Below we will demonstrate why all of these commonly used methodologies introduce a large source of error.

Error of Using Recent Prices

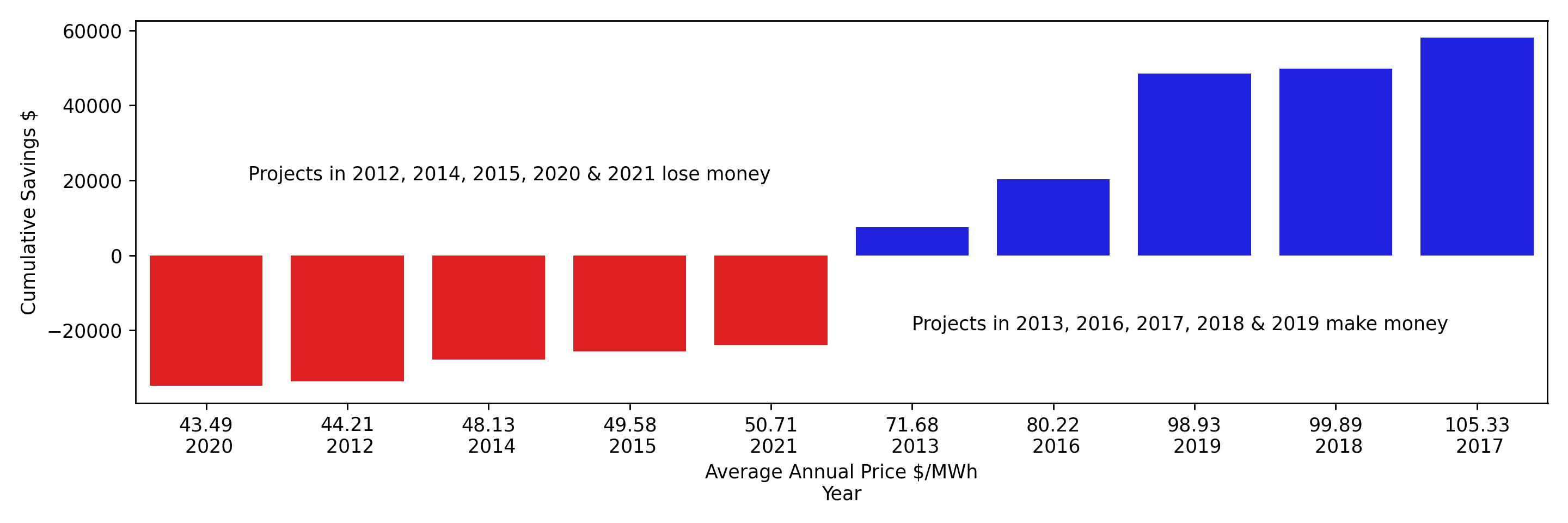

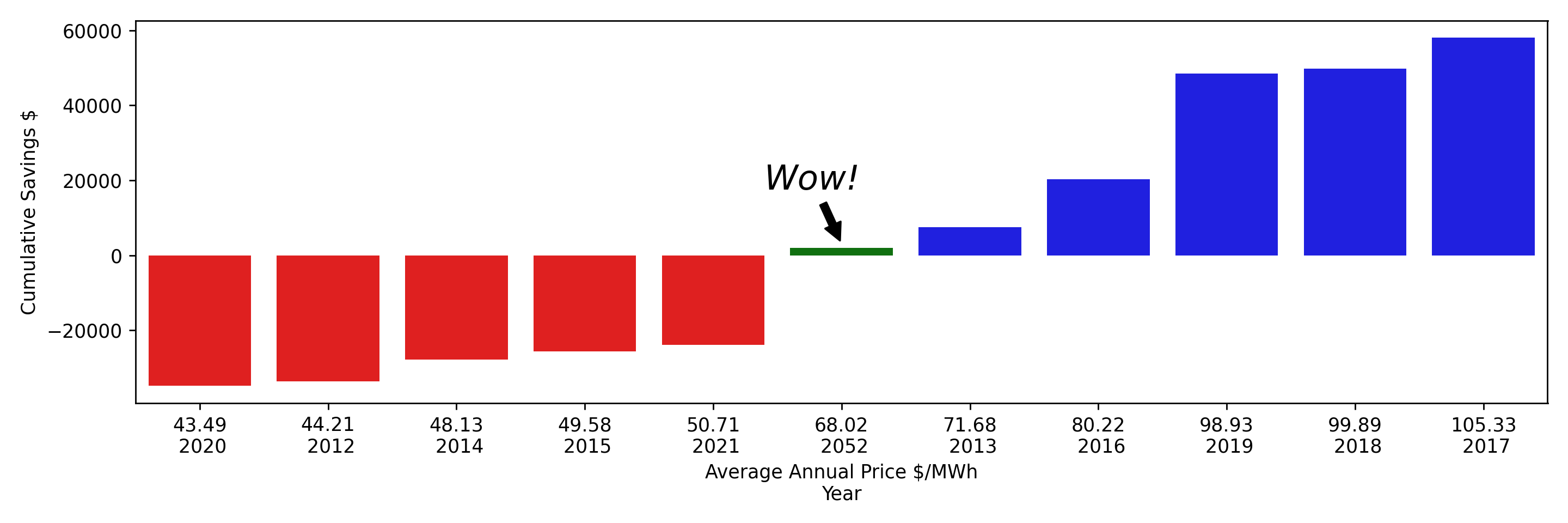

In our example above, we assumed prices at 100 $/MWh. The figure below uses the same financial model with the actual annual average electricity prices for South Australia:

Look at the variance of these results! Around half of our projects lose money, with the other half being profitable.

This variance error that the standard industry approaches are hiding - normally we only get a single estimate, without seeing the spread across different years of price data.

This variance in project performance is only occurring based on when we do our modelling - not based on the fundamental, underlying economics of the project.

We can do better!

Creating a Typical Year Forecast

Creating a typical year forecast requires defining what typical means.

For these forecasts we will define typical as similarity - our typical year forecast will be made of samples of data that are most similar to all the other data.

We can quantify similarity by defining an error metric - the error between statistics measured across all our data and statistics measured across a candidate sample. The samples that minimize this error will be selected and used in our forecast.

For our first typical year forecast, we will create a forecast based on a single statistic - the average price within a month.

The basic idea is as follows:

# Creating a Typical Year Forecast based on the Mean with 5 Years of Historical Data.

# Iterate across each month in a year (12 months in total).

for each month in a year (Jan, Feb ... Nov, Dec)

# Calculate one long term statistic across all 5 years for this one month.

long_term_mean = historical_data[month].mean()

# Iterate across our historical data, selecting this one month,

# 5 months across 5 years, all the same month.

for year in historical_data

sample_mean = year[month].mean()

# Calculate the error of this month versus the long term statistic.

sample_error = absolute(sample_mean - long_term_mean)

# Select the sample with the lowest sample error,

# this is the historical month we will use in our typical year forecast.

selected_sample = argmin(sample_errors)

After following this procedure, we will select 12 monthly samples - one for each month in a year, creating our typical year forecast.

Typical Year Forecast for South Australian Electricity Prices

To further demonstrate the idea, we will first limit ourselves to forecasting a single month - January, for electricity prices in South Australia, using 10 years of historical data.

Let’s first start by calculating our long term statistic - the average price in January across the entire dataset, which is 85.449 $/MWh.

We can then look at what the average price was in each January and calculate the error versus the long term statistic.

This leads us to selecting January 2017 as our typical month of electricity prices:

| year | month | price-mean | long-term-mean | error-mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | January | 25.6153 | 85.449 | 59.8337 |

| 2013 | January | 59.1246 | 85.449 | 26.3244 |

| 2014 | January | 88.8675 | 85.449 | 3.41845 |

| 2015 | January | 34.68 | 85.449 | 50.769 |

| 2016 | January | 50.2573 | 85.449 | 35.1917 |

| 2017 | January | 84.2589 | 85.449 | 1.19009 |

| 2018 | January | 158.757 | 85.449 | 73.3081 |

| 2019 | January | 241.025 | 85.449 | 155.576 |

| 2020 | January | 83.2037 | 85.449 | 2.24526 |

| 2021 | January | 28.7008 | 85.449 | 56.7482 |

We can then repeat the procedure above to forecast the remaining 11 months of the year, ending up with 12 months that make up our typical year forecast:

| year | month | price-mean | long-term-mean | error-mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | January | 84.2589 | 85.449 | 1.19009 |

| 2020 | February | 64.1771 | 71.2239 | 7.04685 |

| 2021 | March | 68.7727 | 66.6858 | 2.08692 |

| 2021 | April | 52.1361 | 64.1214 | 11.9854 |

| 2016 | May | 70.6976 | 70.1316 | 0.565976 |

| 2021 | June | 84.3886 | 81.6753 | 2.71335 |

| 2021 | July | 91.1873 | 94.7737 | 3.58638 |

| 2016 | August | 66.2397 | 64.8625 | 1.37717 |

| 2012 | September | 53.7977 | 54.7594 | 0.961707 |

| 2012 | October | 50.9616 | 52.3186 | 1.35705 |

| 2016 | November | 61.8883 | 57.3279 | 4.56045 |

| 2015 | December | 66.8321 | 67.2765 | 0.444369 |

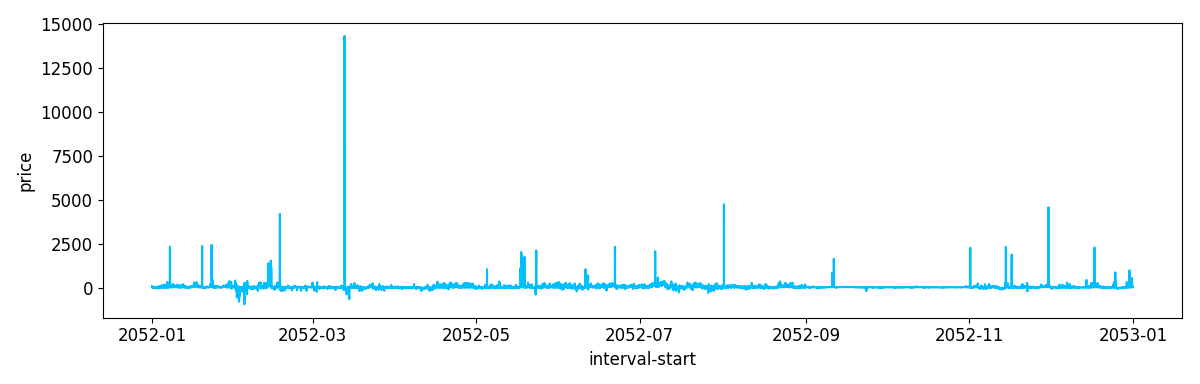

Our typical year forecast, in all it’s light blue glory:

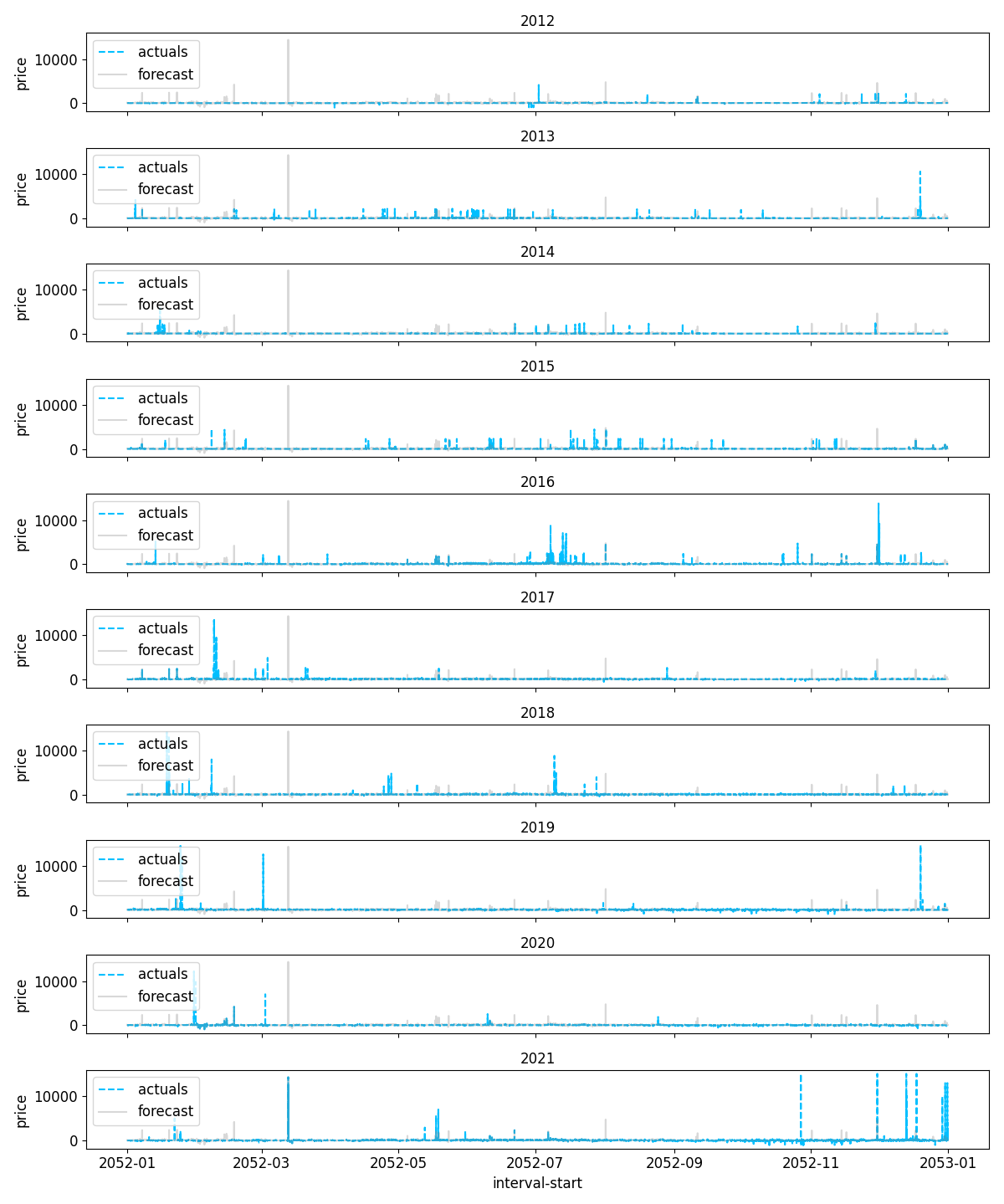

We can compare this typical year forecast to actual historical prices - for the years where we have sampled our typical month from, our forecast directly overlaps the historical data:

Extending the Forecast With More Statistics

Above we only considered the mean when selecting a month. The mean is a measurement of the central tendency of a distribution - using the mean to select a month will mean our forecast has a similar central point to the long term average.

For some energy models, the variance is more important than the average.

The variance is how spread out prices are - it’s important for batteries operating in wholesale arbitrage, as this spread puts an upper limit on the profitability of shifting of electricity between intervals can be.

Our procedure for creating a typical year forecast based on both the mean and the variance is similar to only considering the mean.

We instead calculate two additional statistics (the long term standard deviation and the sample standard deviation), and include them in our sample error:

# Creating a typical year forecast based on the mean & standard deviation

# Iterate across each month in a year.

for month in (Jan, Feb ... Nov, Dec):

# Calculate two statistics - long term mean & standard deviation.

long_term_mean = data.mean()

long_term_std = data.std()

# Iterate across historical data & calculate sample errors,

# using both long term statistics

for year in (historical data):

sample_mean = month.year.mean()

sample_std = month.year.std()

sample_error = absolute(long_term_mean - sample_mean) + absolute(long_term_std - sample_std)

# Select sample that minimizes error.

selected_sample = argmin(sample_errors)

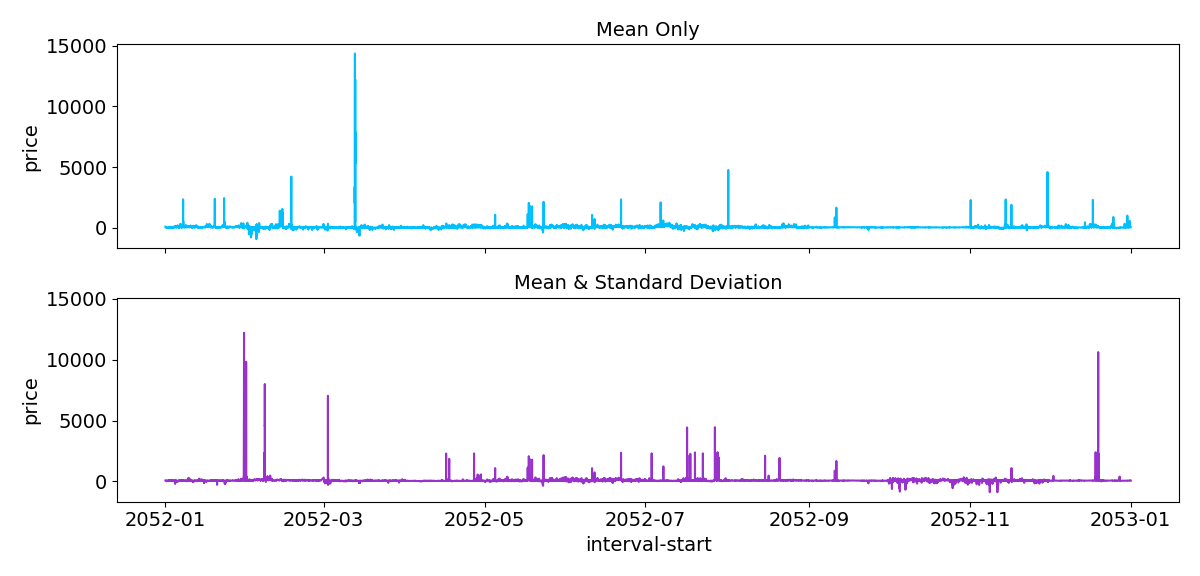

Taking this approach again, we end up with our typical year forecast - different from our previous forecast where we only used the mean:

| month | year | price-mean | long-term-mean | price-std | long-term-std | error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | 2020 | 83.2037 | 85.449 | 519.785 | 504.705 | 17.3251 |

| February | 2018 | 109.17 | 71.2239 | 290.873 | 300.955 | 48.0282 |

| March | 2020 | 46.9517 | 66.6858 | 225.829 | 271.301 | 65.2057 |

| April | 2015 | 39.9493 | 64.1214 | 100.387 | 99.2508 | 25.3085 |

| May | 2016 | 70.6976 | 70.1316 | 132.686 | 133.63 | 1.5091 |

| June | 2021 | 84.3886 | 81.6753 | 96.1186 | 130.305 | 36.8999 |

| July | 2015 | 73.5053 | 94.7737 | 226.191 | 236.491 | 31.5684 |

| August | 2013 | 71.2364 | 64.8625 | 88.1036 | 103.648 | 21.9185 |

| September | 2012 | 53.7977 | 54.7594 | 62.1015 | 75.617 | 14.4772 |

| October | 2019 | 67.3398 | 52.3186 | 92.2279 | 108.001 | 30.7947 |

| November | 2019 | 50.8623 | 57.3279 | 88.3317 | 109.014 | 27.1474 |

| December | 2013 | 79.5734 | 67.2765 | 372.848 | 318.756 | 66.3892 |

We can compare our two typical year forecasts directly:

Typical year forecasting based on both the mean and the variance is selecting months with higher prices - including more of the tasty price spikes that makes Australia’s National Electricity Market (NEM) so interesting for battery storage.

Evaluating the Typical Year Forecast

Let’s return to our original motivating example, with an additional estimate of our project cumulative savings using our typical year forecast based on using the mean (show as 2052 in green):

How great is that!

Our typical year forecast does a fantastic job of cutting through the variance - modelling our project right in the middle of the high variance estimates we get when taking the traditional, industry standard approaches of using historical price data.

No longer are we slaves to the cruel master of time (well, perhaps we still are) - as the years go by, our estimation of project economics will stay stable and consistent, rather than varying wildly based on when we are doing our modelling.

As new price data becomes available, our typical year forecast will change (due to both the long term statistics changing, or recent data being more typical), but the variance from these changes will be minor compared to the massive year on year swings we get with the standard industry approaches.

Discussion

Above we have seen how great our typical year forecast is at reducing the variance of our estimates of project performance - let’s now discuss some challenges and potential extensions to this simple typical year forecasting method.

Challenges

Data Quantity

This methodology requires multiple years of data - if we only have access to a single year, this method is not appropriate.

Alignment

One problem that arises when concatenating interval data from different time periods together is alignment at the intersection - the sample below from the typical year forecast produced above shows the issue - our forecast jumps from Tuesday in January 2017 to Friday 2020:

| forecast | original-timestamps | price | day-of-week-forecast | day-of-week-original |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2052-01-31 23:50:00 | 2017-01-31 23:50:00 | 39.52 | 2 | 1 |

| 2052-01-31 23:55:00 | 2017-01-31 23:55:00 | 39.52 | 2 | 1 |

| 2052-02-01 00:00:00 | 2020-02-01 00:00:00 | 299.2 | 3 | 5 |

| 2052-02-01 00:05:00 | 2020-02-01 00:05:00 | 299.2 | 3 | 5 |

This misalignment will cause issues with the incorrect number of weekdays or weekends in a year - important as energy demand and price has strong weekly seasonality.

This alignment problem also occurs when you don’t use a typical year forecast - for example if you use price data from 2022 with technical data from 2010.

Domain Expertise

Domain expertise is required to setup a typical year forecast - primarily in defining the appropriate statistics.

Using multiple statistics can also require weighting - for example if the standard deviation is orders of magnitude higher than the mean, we may want to weight the mean higher.

Extensions & Improvements

Higher Frequency Sampling

In the examples above we have selected samples on a monthly basis - it is possible to instead select samples on a different frequency, such as week of the year (52 weeks) or day of the year (365 days).

More Statistics

One advantage of this methodology are flexibility of statistics we choose - unlike a loss function for a neural network, they do not need to be differentiable.

For example, we could use statistics like:

- mean, median, mode,

- number of time periods above a threshold price,

- number of negative prices.

This is an exciting feature of typical year forecasting - the flexibility and simplicity of using any statistic that aligns with what your technical and financial models need to align with your business goals.

Summary

In this post we introduced typical year forecasting - a flexible, powerful forecasting method suitable for use in energy project business case modelling.

Typical year forecast address a hidden flaw in the price assumptions commonly used in industry - the large errors introduced by using recent price data.

A typical year forecast addresses these issues by selecting historical price data that is most similar to all the historical data.

Typical year forecasts have the following advantages:

- simple to create - no machine learning, gradients or iterative calculations,

- interpretable - easy to understand why one sample is selected over others,

- realistic - the forecast is made from actual historical data,

- domain flexible - can be used with any time series (not just electricity prices),

- statistically flexible - can use a range of statistics to define what typical means.

A typical year forecast has the following disadvantages:

- data quantity - requires at least 2 years of historical data,

- domain knowledge - requires selecting & weighting of statistics based on problem understanding.

Further extensions on the methods shown above include:

- higher frequency sampling on a weekly or daily basis,

- using a variety of statistics to define similarity, such as the number of price spikes or the number of negative prices.

Thanks for reading!

If you enjoyed this post, make sure to check out Measuring Forecast Quality using Linear Programming.

You can find the materials to reproduce this analysis at adgefficiency/typical-year-electricity-price-forecasting.