Inertia in Electricity Systems

Inertia is a common criticism of the energy transition - is it valid?

Inertia is a common criticism thrown at our current energy transition towards renewables.

This post explains what role inertia plays in an electricity grid, and the clean solutions we have to the inertia problem.

Synchronous Generators and Inertia

Large, fossil fuel and synchronous generators have historically dominated electricity grids. A synchronous generator operates with high inertia, which is valuable to the grid. Any disturbance to the grid must work against all the inertia of the grid - you can think that the massive, hot, spinning synchronous generators ‘push back’ against disturbances in the grid.

Fossil fuel generators burn fossil fuels to produce high temperature and pressure gases (steam in steam turbines, air in gas turbines). These high temperature and pressure gases can be used to drive turbines. The rapidly spinning turbines are connected to alternators via a rotor. The alternator generates AC electricity.

It’s the rapidly spinning turbine that gives synchronous generators high inertia. Once this rotor is spinning it’s hard to get it to stop. The speed at which the shaft & alternator needs to spin at is directly proportional to the desired grid frequency. In fact the grid frequency is the result of the speed that all these synchronous generators spin at. The frequency of electricity generated by a synchronous generator is given by:

# poles refers to the poles of the alternator

# 120 converts from minutes to seconds and poles to pairs of poles

frequency = speed * number_of_poles / 120

A renewables based electricity system is composed of small-scale, clean and asynchronous generators.

Wind and solar are asynchronous generators. Wind turbines also use rotation to generate electricity, but spin at variable speeds (i.e. asynchronously relative to the grid frequency) and at slower speeds than synchronous generators.

Photovoltaic solar panels and batteries have no moving parts at all - electricity is generated as DC and put through an inverter and transformed into AC electricity.

The Value of Inertia to the Grid

The grid is an interconnected system. Changing grid frequency requires changing the speed of every synchronous generator connected to the grid. This interrelationship is useful during times of supply & demand mismatches. Any imbalance needs to work to change the speed at which every generator on the grid spins. If these generators posses a lot of inertia, then the imbalance needs to work harder to change the grid frequency.

This is the value of inertia to the grid – it buys the grid operator time to take other actions such as load shedding or calling upon backup plant. These other actions are still needed – inertia won’t save the grid, just buy time for other actions to save the grid.

Clean Solutions for Inertia

So now we understand that fossil fuel generators have inertia and how it is valuable to the grid (it buys the system operator time during emergency events). What does this mean for our energy transition? Do we need to keep around some fossil fuel generators to provide inertia in case something goes wrong? The answer is no.

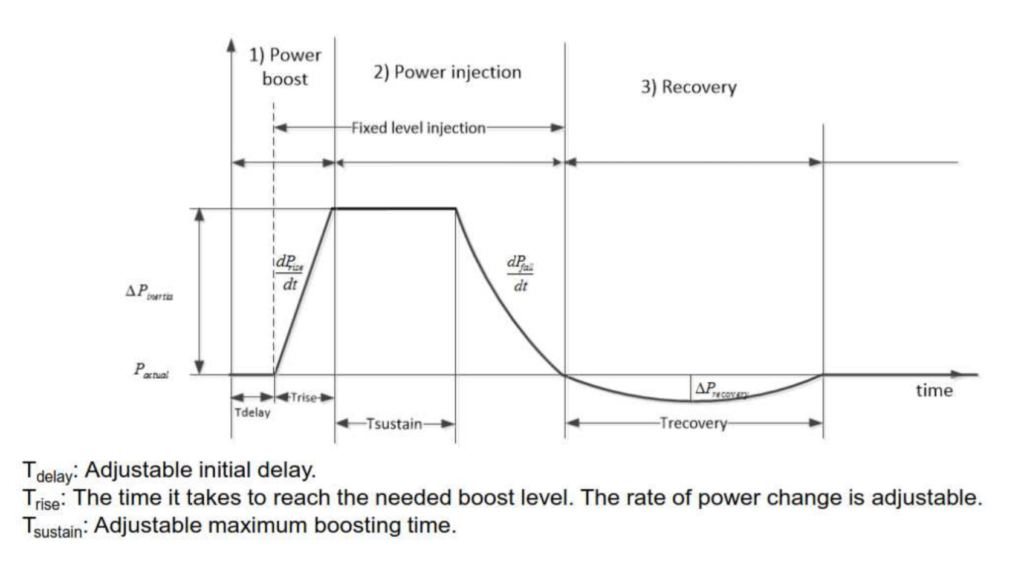

Modern wind turbines can draw upon kinetic energy stored in the generator and blades to provide a boost during a grid stress. This ‘synthetic inertia’ has been used successfully in Canada, where wind turbines were able to supply a similar level of inertia to conventional synchronous generators.

Figure 1 – Conceptual fast frequency response from a wind turbine

Figure 1 – Conceptual fast frequency response from a wind turbine

Photovoltaic solar and batteries also have a role to play. Both operate with inverters that convert DC into AC electricity. The solid-state nature of the devices means that they operate without any inertia. Yet this solid-state nature allows inverters the ability to quickly change operation in a highly controllable way.

Inverters can quickly react to deliver whatever kind of support the grid needs during stress events, in a way that is superior to hot, spinning turbines.

Summary

In summary - wind, solar and batteries all have a role to play in replacing the inertia of fossil fuels. Clean technologies are ready to create a new electricity system.

Crucial to the energy transition is incentivizing the services that our grid needs. If inertia is valued by system operators then it needs to be incentivized.

The level of support could be logically set so that the level of inertia on the grid will remain at the same level as our old fossil fuel based grid. That way, no one can complain (but I have feeling some may still).

Thanks for reading!